The Specialists

UNIQUELY CHELSEA: An area dedicated to some of the most unique minds of the past century and more, who have been residents of Chelsea and found inspiration in the same ambience and character as the community today.

Chelsea: The home of Ian Fleming and his 007 legacy

A brief history of Ian Fleming, James Bond and Chelsea locations:

As No Time to Die, the 25th film in the James Bond series, is now on worldwide release, the last outing for Daniel Craig as eponymous M16 agent, 007, this film has been lauded as nodding to the inaugural Bond adaptations, which reflected the essence of Ian Fleming's source novels.

Whilst green screens, technology and action have become a foundation of franchise movie making, the leisurely shooting days at Pinewood or location visits from Barry Norman so synonymous with Bond are something of the past. However, whether due to the pandemic driven release delay, the sad passing last year of the original, Sir Sean Connery, or the end of Daniel Craig's tenure, No Time to Die has prompted renewed fascination in the world of famed character creator, Ian Fleming, and the world and areas he inhabited, so often mirrored by his iconic creation, 007.

Ian Fleming - Chelsea:

Ian Fleming was born 28 May 1908 in Westminster.

His family moved to 113-117 Cheyne Walk, Chelsea when he was still at school. The premises were originally three workman's cottages, which Fleming's mother had converted into a single residence.

In the early 1950's Fleming moved back to Cheyne Walk, having moved away during war time. He returned but to 24 Carlyle Mansions: the red brick Victorian building is dubbed 'The Writers Block' because it previously inhabited residents including T.S Eliot, Somerset Maugham, Henry James. He lived there between 1950 and 1953: It was at this address he conceived the Bond novels with his first Casino Royale, written in 1953, the first of 12 novels based on the stories of the suave, debonair British spy, 007. It was a success with three print runs commissioned to cope with demand.

In June 1961, Fleming sold a six month option on the film rights to his published and future novels to Harry Saltzman.

The Times ranked Fleming as 14th on the 'The 50 Greatest British writers since 1945.

James Bond - Chelsea:

James Bond's flat is mentioned in three novels: Moonraker, From Russia With Love, Thunderball.

Moonraker: Arguably the most personal of the Bond books, taking place wholly in England, Fleming describes Bond's flat as 'the ground floor of a Regency house in a small Chelsea Square with Plane trees.' He develops this later by describing it as also 'including a basement, that the sitting room has a bay window overlooking the square and that there are steps running up to the front door.'

There has been much debate which Chelsea square it could be (Markham, Carlyle, Paulton, Wellington, Chelsea, Royal Avenue)

Thunderball: One other clue when in this book, Fleming describes his spy character as swerving out of the square, 'into the Kings Road, and then fast up Sloane Street and into the Park.'

From Russia With Love: Bond's home is described as having a 'long, big windowed sitting room' and is also said to be 'booklined.'

No.25 Wellington Square:

Famed author and researcher, William Boyd, who wrote the Bond continuation novel, Solo, meticulously researched Bond's address and fell on the only possibility from the descriptions being Wellington Square - No.25 - this was the home belonging to Sunday Times literary critic, Desmond MacCarthy, when Fleming worked in his early years at the newspaper as foreign manager.

Bond filming locations - Chelsea:

Skyfall: When M returns home to find Bond alive and ready to return to services, the exterior was shot at 82 Cadogan Square. This address was actually the home of the late legendary Bond music composer, John Barry.

Dr No and Live and Let Die: Both interiors were shot in Chelsea.

N.B Bond's home featured in Spectre is not in Chelsea, it's a regency building in Notting Hill.

Bond: Behind the scenes c/o Box Galleries, King’s Road, (and the photographer Terry O’Neill)

Agatha Christie's London. Her residencies: 22 Cresswell Place. Swan Court, Chelsea.

Agatha Christie's first experiences of London began as a child - travelling to the West End to see family and theatre runs - and coincided with the invention of the first electric tram service in Ealing. The day it first ran in 1901, Christie, then aged 11, wrote a four versed poem, which was published in a local newspaper and became her first ever piece in print.

Through Christie's life she saw London through many historical moments -including both World Wars - and its transformation over the decades through Victorian society to Swinging Sixties. Christie imbibed the vibrancy and change of her surroundings featuring it's streets, luxury hotels and decadent nightlife in her novels. From 'the 4:50 from Paddington' opening through the hustle and bustle of Paddington Station to the Man in the Brown Suit, when the narrator travels from Gloucester Road to Hyde Park Corner, to Claridges hotel whose art deco glamour mirrors the aesthetic described in the Murder on the Orient Express, Christie's heart however was in Chelsea, where she finally settled to write some of her most renowned works.

Having married her first husband, Archie Christie, during WW1, and living in the NW1 area, whilst he was in the Air Ministry, they later divorced and by the end of the 1920's Christie, by now a successful author, used her earnings to independently buy 22 Cresswell Place, Chelsea, SW10. Christie had always had a passion for houses, often using them to conjure up many of her 'who-dunnit' narratives and continued to buy, redecorate and later sell many properties throughout her life. However, Cresswell Place, Chelsea always remained under her ownership (inspiration for short story 'Murder in the Mews'): The tiny, almost doll-size proportioned house, is tucked away down a quiet, narrow, cobble-stoned lane, with other similar properties. Mews houses were originally built as the stables and coach houses, to accommodate the horses and carriages for the nearby grander town houses. Agatha recollects: 'When I bought it, it had stables still, with the loose-boxes and manger all round the wall, a big harness-room also on the ground floor … A ladder-like stair led to two rooms above… With the help of a biddable builder it had been transformed… The harness-room was turned into a garage... Upstairs the bathroom was made splendid with green dolphins prancing round the walls and a green porcelain bath; and the bigger bedroom was turned into a dining-room, with a divan that turned into a bed at night.'

After purchasing and redesigning Cresswell Place, and later married to her second husband, Sir Max Mallowan, the Christies moved to Swan Court, Chelsea. The one bed flat within the beautiful art deco building was their home for 28 years - 1948 till her death in 1976 - and was the place she used to write her enduringly successful play, The Mousetrap, a global phenomenon which is still running in West End theatres today. Whilst in Swan Court she also wrote Poirot novel, The Third Girl, (published 1966), it is thought the plot actually is set in Swan Court, as well as her eponymous who-dunnit novel, Death on the Nile, and Witness for the Prosecution (a play 1953) - turned by MGM into the first of the Christie movie adaptations starring Marlene Dietrich. (See below section).

Whilst living in Swan Court, she liked to frequent the area for ideas and inspiration. The Cross Keys Pub(the oldest pub in Chelsea 1708) now inhabited by 50 Cheyne has a blue plaque for literary/art connections, where Christie and contemporaries such as Dylan Thomas, Turner, Sargent passed through the doors.

Chelsea also featured in her novels; The Pale Horse, a detective fiction published in 1961 begins with the protagonist, Mark Easterbrook, spotting a fight between two girls in a local Chelsea cafe.

Both these residential Chelsea addresses continue to be modernised and redecorated for new owners today inspired by the legacy of one of Britain's most well known authors of all time.

Molly Parkin b. 1932 (Wales) Place of residence: Old Church Street, Chelsea circa early 60’s, World’s End - present.

Painter,(her work is collected by The Tate) novelist, former fashion editor (Sunday Times fashion editor of the year in 1971, Nova), 60’s doyenne, bohemian. Parkin embodies all the adjectives that have come to represent the legendary ‘Swinging sixties’ time in Chelsea; infact it was after the opening of her own shop on Radnor Walk, in 1964, when her self designed/created clothing collections instantly sold out, that a journalist from US paper, Newsweek, came to report on the ‘colourful’ fashions of London and first coined the term, ‘Swinging London.’

Dame Vivienne Westwood (8th April 1941-29 December 2022)

The famed British fashion designer and social/political activist who was largely responsible for bringing modern punk and new wave fashions into the mainstream is synonymous with the King’s Road, Chelsea. Growing up to a working class family, she took courses in jewellery, silversmith and art but was concerned she couldn’t make any living from it so became a primary school teacher, selling her distinguished jewellery on weekends at a stall at Portobello Market. In the early 60’s she met Malcolm Mclaren, music manager to the Sex Pistols, Westwood would create clothes with Mclaren, which garnered notoriety when worn by Sid Vicious and others in the group. In 1971 they opened Let It Rock, a garage at the back of the current World’s End space; Westwood remarked, ‘I was messianic about punk, seeing if one could put a spoke in the system in some way.’ The architects of the punk movement in Britain, Westwood became the central force in the partnership, re-naming the shop to SEX in 1974 - designing clothes that showed the deconstruction and said ‘it’s ok not to be perfect.’ Think t-shirts slashed constructed with safety pins, hand written labels, see-through big knit mohair jumpers, pvc.

Historical costumes and references played a large part in Westwood’s design inspirations - as she evolved from punk into the 80’s showing independent collections in Paris and London - from New Romantics (1985), The Pagan Years (1981), Pirate, Savages, Witches and Worlds End (1984) collections. From 1985 she took inspiration from the ballet, ‘Petrushka’ to design the mini-crini, an abbreviated version of the Victorian crinoline; it was later described in the press as a combination of two conflicting ideals - the crinoline, representing a ‘mythology of restriction and encumbrance in woman’s dress’ and the miniskirt, representing an ‘equally dubious mythology of liberation.’ She continued to challenge the status quo not just in design silhouette - often blending romantic flushes and historical references with harder edged political messages - but also through her voice on social issues such as the environment and gender equality that she used as a a backdrop commentary to her runway shows.

Infact even as her design label grew into a big business empire, she never lost her activist streak; in 1989 she posed on the front cover of Dazed magazine as Margaret Thatcher as well as remixing and inverting imagery drawn from the monarchy in collections - such as the infamous ‘God Save the Queen’ slashed tee-shirt. She received both an OBE and CBE from the Queen in 1992, 2006 respectively.

The Worlds End Shop became ‘Worlds End’ after Sex and Seditionaries in 1979, the title it still carries today: According to Westwood in her 2014 memoir, ‘Malcolm (Mclaren) and I changed the names and decor of the shop to suit the clothes as our ideas evolved.’ '

According to architect, David Connor, ‘we decided the store was going to challenge time and space, which is an amazing concept for a tiny shop.’ Uniquely designed to reflect the whimsy and romanticism of Westwood’s, A/W81 Pirates collection, the slanted floor was designed like a galleon of a ship and facade featuring a 13 hour clock ticking backwards.

Dame Mary Quant (11 February 1930)

With a 2021 new documentary film out revisiting the influence and legacy of famed British fashion designer, Mary Quant, it's evident that with her distinctive style, revolutionary design vision and ability to 'brand' her company during the 60's, she was well ahead of her time. An instrumental figure in the 1960's London based Mod and youth fashion movements, she made famous the 'miniskirt' - (the then known 'short skirt' she named after her favourite car) - but is also synonymous with her first-of-its-kind, Chelsea located 'Bazaar' boutique, and as a pivotal part of a larger cultural zeitgeist, Swinging Sixties London.

Well known London based journalist and Sunday Times associate, Ernestine Carter, wrote at the time: 'It is given to a fortunate few to be born at the right time, in the right place, with the right talents. In recent fashion there are three: Chanel, Dior and Mary Quant.'

Mary Quant - Fashion

'The fashionable woman wears clothes. The clothes don't wear her.' Mary Quant

Mary Quant was born in Blackheath, London (1930) and attended Goldsmiths College, where she studied illustration, before learning her craft in a high end millinery in Mayfair called 'Erik.' Hats were big business in the early fifties: the majority of women wore them daily , still dressing to suit the post war austerity mood.

Quant started to design her own clothing collections: practical, often waist less, androgynous clothes in tweed, gingham, grey flannel, and Liberty print, fabrics then usually associated with men or childhood.

Harpers Bazaar caught on (see below) featuring a full Quant editorial, including a sleeveless day time tunic worn over culotte trousers and 'spotty' pattern pyjamas.

Collections continued with daring, hip items previously unseen: PVC black mackintoshes, hot pants, zip fronted shift dresses, daisy patterned tights, dungarees, trousers for women and midriff bearing tops, but most revolutionary was the jersey fabric boom she heralded that went on to permeate the 70's continuing till today. She incorporated it into different shapes and colours including on collars, sleeves, buttons and skirts in different cuts. Practical, affordable and crease resilient, the jersey dress became a driving force in the democratisation of style.

It wasn't till 1965 that the mini skirt revolution came about - whilst it must be acknowledged that there is no evidence Quant actually invented the mini (most people credit it to French designer Courreges) she invented the name (after her favourite car) as previously it was just called 'a short skirt' and made it a global sensation, starting of course on the King's Road.

She acknowledged in a later newspaper interview (1977) that 'graduating from an arts college rather than a fashion school had been a blessing 'because in those days fashion stemmed down from the top and watered down to the working classes, whereas she always believed fashion should start from the bottom.' It was this desire to make fashion fun, accessible and unconventional, which caught the zeitgeist of the new generation and heralded in a new dawn.

The designer's legacy remains a fundamental part of the 20th Century women's liberation story and the democratisation of fashion.

Mary Quant - Chelsea

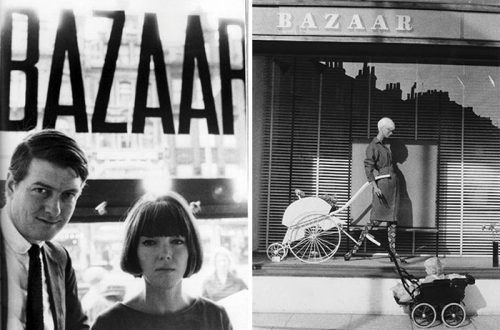

Married to her fellow Goldsmiths student, Alexander Plunkett Greene, they became the focal point of the 'Chelsea set' - a cool, creative nucleus beginning to emerge in the mid 50's. In 1955, along with a friend, the pair opened the revolutionary 'Bazaar' Boutique - a club meets shop - which sold everything 'bizarre and from the bazaar.' From Quant's own self taught designs to jewellery and accessories commissioned from their art school friends, the space at 138A King's Road heralded in a new era of 'boutique owners' as the small, useful shops of the past disappeared. Whilst the King's Road suddenly became a magnet for the beautiful and (often) wealthy, Quant's shop welcomed a complete melange of clientele from royalty to writers, to directors and artists with the Rolling Stones and Grace Kelly between.

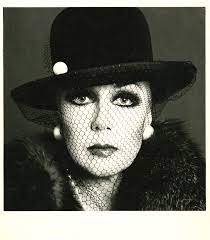

Quant heralded in the age of the Saturday afternoon shopping parade as 'the thing to do.' With eccentric window displays full of quirky model poses, motorbikes as props and a buzzing restaurant scene downstairs, shopping became 'sexy' and 'Bazaar' became the only place to be. The buzz around 'Bazaar' was noted by the other fashion 'Bazaar' - the magazine Harpers Bazaar - who first spotted Quant's vision and potential. A full spread interview in the July 1957 issue just before her revolutionary and image defining hair crop by Vidal Sassoon, 'photographed her in offbeat shades of violet and blue,' - paradoxically whilst her highly individual style made her the figurehead of her own brand, her non-conformist outlook was by its very nature 'anti-brand.'

With the introduction of a cheaper wholesale line in 1963, and in 1966 her instantly recognisable funnily packaged make up, jewellery and coloured tights, she was decades ahead of her time in introducing a type of licensing, a way of making her items available to the mass market as well as a form of branding in her signature flower design logos and packaging - a way fashion does business still today.

By the time of the miniskirt in the mid 60's, youth was setting the pace and women longed to be 'quantified.' It was also a time where the entrepreneurial, bright young thing focus had moved from the States to London, specifically Chelsea.

Bond: Behind the scenes images- c/o of Box Galleries King’s Road and photographer Terry O’Neill.